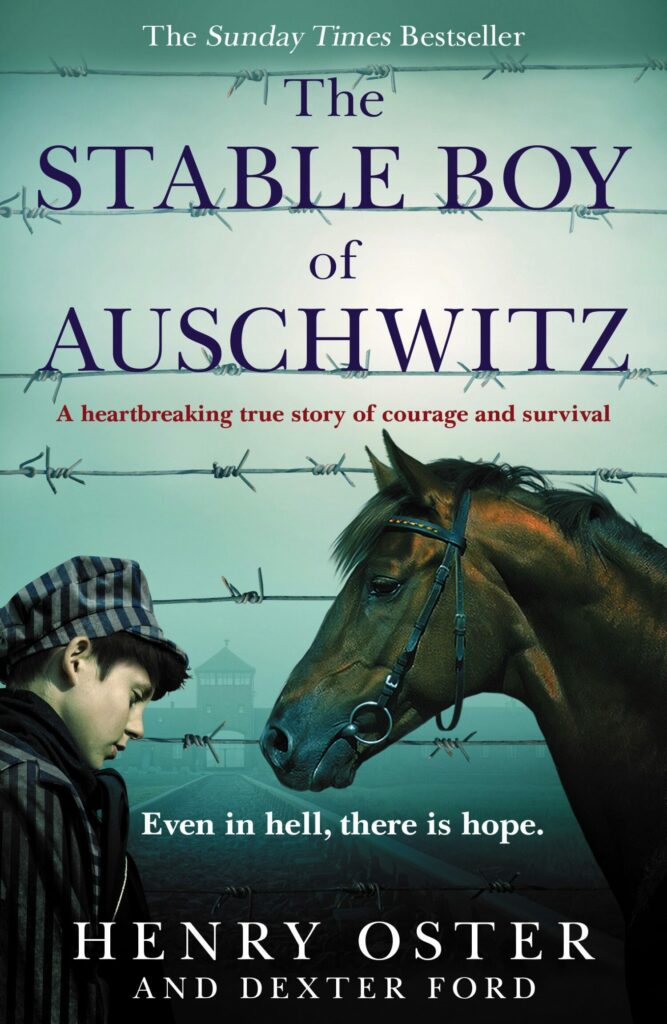

The Stable Boy of Auschwitz Exclusive Extract

An exclusive extract of The Stable Boy of Auschwitz by Henry Oster and Dexter Ford.

To celebrate the publication of The Stable Boy of Auschwitz, we’re sharing an exclusive look at the first chapter of this incredible memoir…

A long time ago, I was a five-year-old German boy. Heinz Adolf Oster. I was an inquisitive, energetic little wise guy with a shock of black hair, a double dose of curiosity and a limited ability to stand still for any length of time.

One of my earliest memories is of walking on the tree-lined sidewalks of Cologne, the majestic, historic German city that was my home, going out with my father to vote in the 1933 German national election. That was, of course, the election that allowed Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Party—the Nazis—to seize power in Germany.

I had no idea of how important that day was, or what that elec- tion would lead to. Nobody did, probably not even Adolf Hitler himself. But I do remember my father—Hans Isidor Oster—taking my hand as we walked out of our apartment, and down the street to the voting booth.

My father was tall, serious, thin and respected. People on the street would recognize him, smile, tip their hats to him. Friends stooped down to see me, his little boy, all dressed up like Little Lord Fauntleroy, on our adventure. I remember he smoked cigarettes constantly—it seemed to make him more grand, more mature, more important.

It was a rare treat, getting to go out with my dad, just the two of us. He was the manager of several small department stores, and he was usually very busy, so I spent much more time with my mother than with my father.

I remember that after we left the polling place, he took me to a confectioner’s shop to get schlagsahne—vanilla-flavored whipped cream—which was kind of like going out for ice cream today. I was very happy. It was a big day for me.

I was an only child. I lived with my mother and father in this cosmopolitan, elegant city in western Germany. Cologne is known for its ancient Gothic cathedral, the Dom, its twin towers of lacework masonry thrusting what seemed like miles above the city.

We didn’t worship in the Catholic Dom, but we were, first and foremost, a good German family. We had no reason to feel that were any less German than anybody else. My father was a veteran of the German Army, the Wehrmacht. He had fought in the Great War—World War I—just like millions of other German men. He had been wounded in the war: he had a scar on his cheek where a piece of shrapnel had hit him during an artillery barrage. He had been awarded a medal for bravery. He had no reason not to fight in the defense of his country, right or wrong—to fight for his Fatherland. Like any other good German.

The only thing that was different about us was that we were Jewish. This, at the time, wasn’t a big deal to me. The only way that I could sense any difference between myself and the other German kids I knew was that I went with my family to synagogue every Friday night, instead of going to church on Sunday. And I went to a German Jewish school, where we were taught Hebrew, along with all the other usual subjects. But I had no sense that we were different, no better or worse, than any other German family.

It was a comfortable, normal life. I was just a restless German kid, with a nice family, in a busy German city. But when Hitler and the Nazis came to power—just about the time I was old enough to have any idea of what was going on around me—everything started to go haywire.

The first time I began to feel that there was anything wrong—my first experience of being singled out, being different, being perse- cuted—was my first day of school, in 1934.

Like every other kid, I was frightened, a little apprehensive. I was six years old now, and I was going out, into the unknown world, away from my mother and father for the first time, ready or not.

My parents walked me to school; I was carrying, very seriously, a little leather backpack containing a tiny blackboard, a piece of chalk on a string, and a sponge to use as an eraser. I was wearing knee pants, stockings and a little hat, like a beret, which identified me as a first-year student.

Like all the other children, I carried a huge cardboard cone that my parents had given me. It looked like a megaphone or a dunce cap, and was filled with all kinds of lovely things—candies and little toys. It was a German tradition to send kids off to their first day of school with this—we called it a Zuckertüte, or “sugar cone”—to help us feel more comfortable as we went into this strange new world. We weren’t allowed to open them—they were tied with red cellophane at the top, to keep us from getting at the goodies inside—until we got home from school. It was a sort of reward, something to look forward to. Mine was almost as tall as I was, or at least that’s the way it felt to me.

But when we came out of school that day, holding our precious sugar cones, we were attacked by a gang of Hitler Youth, the Deutsches Jungvolk and Jungmädel. They were a big, noisy mob, waiting outside on the sidewalk, boys and girls not much older than we were. They were all very proud of themselves, all dressed up like little Nazi Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

We were scared to death. Some of my classmates were crying. We were all little kids, just six years old. And now, after our first nervous day of school, we were being attacked by this screaming Nazi mob for no reason.

My parents—and all the other Jewish kids’ parents—were waiting outside the school to pick us up and walk us home. But there was nothing they could do to help us. They had all been shoved out of the way by the Hitler Youth leaders: young toughs in their teens and twenties.

I remember looking up and seeing a sea of uniforms and angry faces. The people were yelling and taunting us, these furious kids with their Nazi neckerchiefs, all with the same swastika slides at their throats. The boys had daggers on their belts. They were just kids, ten to fourteen years old, but they each had their little Nazi knives.

In the background we could see the Nazi organizers, and the proud parents of the Hitler Youth, standing with their arms crossed. They were obviously enjoying this, watching their children showing the little Jewish kids just who was who and what was what.

The children threw rocks at us. They hit us with sticks. We were all forced to run this gauntlet to escape, to get through to our parents and safety.

The Hitler Youth paid special attention to attacking our Zuck- ertüten. They bashed at them with their sticks, trying to knock them out of our hands. And when one broke open, they all scrabbled on the ground to steal our candies and toys.

Eventually, a couple of Cologne city policemen, who were not necessarily Nazis then, showed up and stopped the attack, giving me and the other Jewish kids enough time and space to make it through to our parents.

None of us was seriously hurt—just some scrapes and small cuts, a little bit of blood here and there. But we were all shocked.

I had gone to school that morning, full of excitement and anticipation, anxious about how well I was going to do in the classroom. When I finally made it home that afternoon, the world was a much darker, more dangerous place. My life would never be the same again.

-

Ebook

-

Audiobook

-

Paperback