Objects that speak a thousand words

‘Why am I not white?’ Nan came and sat on the edge of my bed. A tender finger brushed against my cheek. ‘Everyone in this house is white. Why am I Black?’

Trunk Boxes

My parents returned to Nigeria from England in the sixties with their belongings stuffed into beautiful trunk boxes. I still remember the autumnal morning when the movers arrived and spent all day heaving everything we owned into containers, ready for the long journey to Africa. Back in Nigeria, where my life changed beyond all recognition, there was something nostalgic about peeking at the boxes in my parents’ bedroom. Although a constant reminder of what I left behind, they also had the power to transport me back to happier times.

The Grater

I grew up in a culture that expected girls to do most of the domestic work, which meant I did a lot of cooking. Some of the traditional meals required extensive preparation. One of those, Ikokore, a favourite dish of the Ijebu people, a sub-tribe of the Yoruba ethnic group, was a family favourite. Around the age of fifteen, my grandmother decided it was time I learnt how to prepare it from scratch. Ikokore was made with grated water yams. The grater, made of holes hammered into a simple sheet of metal, was nailed to a plank of wood. You straddled the plain plank end and sat with it between your bottom and a stool. This kept its weight counterbalanced while you grated away. Like all true Ijebus, I loved Ikokore and was excited to prepare it. I cut, peeled and rinsed the yams with minimal fuss. Next, I cinched the grater between my rear and a stool, picked up the first piece of yam and started grating.

Five minutes into the task, I realised I had an enormous problem. ‘Mama, my hands are itching,’ I whined. Yams contain saponins which irritate the skin and both my hands were lathered with the gelatinous gratings. ‘Grate faster. The quicker you finish, the better,’ my grandmother said. I doubled down on the task, and with gritted teeth, pushed the yam through the grater. By the time I finished, I felt like a million sand flies were taking tiny bites out of my flesh. I washed my hands, but it made no difference. I soaked them in water with no effect. ‘They are still itching!’ I moaned.

‘Here,’ Mama offered some palm oil, ‘rub that all over your hands, then sit near the wood fire and hold your hands up to the heat.’ The sceptic in me didn’t believe Mama’s remedy would help, but I was too desperate not to try. I took the oil and rubbed it in. Then I hunkered down next to the fire and held my hands up, not so close that it burned, but near enough that the soothing warmth seeped into my fingers. Soon, the itching subsided. Ten minutes later, I stared at Mama in wonder, realising I had stopped itching altogether. How did she know this stuff? The elders in the family seemed so full of knowledge and wisdom, even though none of it was in a recorded form. This included knowledge of a host of remedies for various ailments. I wondered how much scientific experimentation had gone into developing that knowledge and was more than a little saddened that this ancient know-how was vanishing in the wake of modern science.

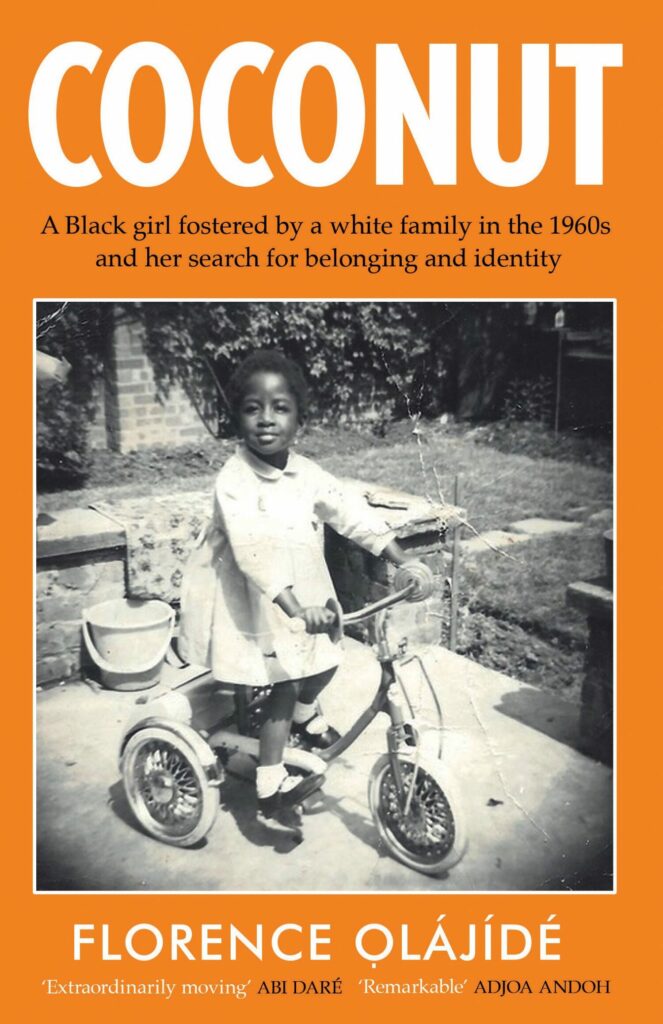

Coconut

Florence Ọlájídé

‘Why am I not white?’ Nan came and sat on the edge of my bed. A tender finger brushed against my cheek. ‘Everyone in this house is white. Why am I Black?’

-

Ebook

-

Audiobook

-

Paperback